Carmen Rodríguez | Sep 08 2015

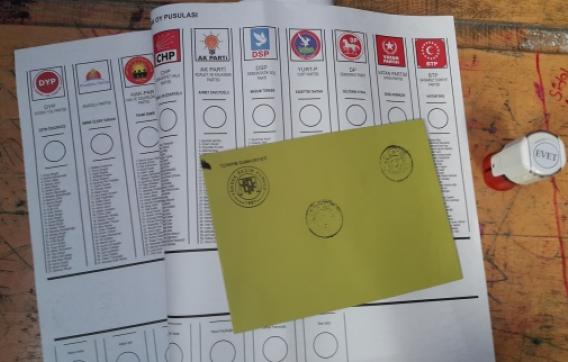

Following the general elections held on 7 June 2015 the AKP lost the absolute majority with which it had governed through the previous three parliamentary terms. Four parties managed to pass the high 10% electoral threshold. Winning a share of the seats in parliament - besides the AKP - were the centre-left CHP party, the ultra nationalist MHP and the pro-Kurdish HDP party, which expanded its electoral base by incorporating demands over social issues and human rights which appealed to a heterogeneous group of voters, thereby overcoming the traditional Turkish-Kurdish cleavage.

Ahmet Davutoğlu was entrusted with the presidential mandate by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to form a workable coalition government. But major differences between the four parties represented in parliament meant huge obstacles to the formation of a government. In fact, soon after the elections Erdoğan expressed his wish to see the elections repeated. Throughout the campaign the president had held rallies in favour of the AKP, violating the constitutional requirement the president maintain a position of neutrality towards political parties. Although the possibility of a grand coalition between the AKP and the CHP was floated - an option that seemed to be supported by the country's principal economic forces - ultimately no agreement was reached. Among the key issues that prevented this rapprochement were the CHP's demands, such as for in-depth investigations of the corruption cases involving the AKP or limits on the role of Erdoğan in the work of the Turkish executive.

After Davutoğlu’s consultations to form a government failed, Turkish electoral tradition impelled the president to confer the mandate to form a coalition government on the second most-voted-for party – which is, in fact, what the CHP requested. However, once the 45 day deadline to form a government - granted to parties by the Turkish constitution - had passed, the president decided instead, in keeping with his aforementioned preferences, to call new elections.

The elections will take place on November 1st amidst a climate of maximum tension and uncertainty. Adding to this is the situation in neighbouring Syria and the unforeseeable impact of Turkey’s role in the its war. The conflict between the PKK and Turkey’s military forces in the country’s interior flared up again seriously during the summer. There is a lot of speculation about the reasons for this resurgence of the conflict. The Turkish health minister Mehmet Müezzinoğlu declared that “chaos exists in Turkey because it is not ruled by a presidential system.” According to this interpretation, if the AKP had won the absolute majority needed to change the constitution, Turkey would not be in the situation it finds itself in today. The truth is that significant majority Kurdish regions of the country have been deemed “special security zones” off limits to civilians, which recalls the infamous state of emergency which was applied to 13 provinces between 1987 and 2002 and which ended as a result of the accession negotiations between Turkey and the EU. The HDP leader Selahattin Demirtaş has declared that in these conditions it is impossible to campaign, let alone hold elections, in the east of the country, given the spiral of violence in the region and inadequate guarantees that voting can take place freely and safely.

The AKP and Erdoğan are seeking a fourth absolute majority. What is not clear this far out from the elections and in spite of the opinion polls published to date is whether the Turkish nationalist vote in reaction to the PKK attacks will suffice. It is also unclear whether the HDP will again make it past the 10% electoral threshold, which was the principal reason for the AKP losing its absolute majority.

Last but not least, the latest police raids carried out against the Koza Ipek Holdin group, which includes the Bugün and Millet newspapers and the BugünTV and Kanaltürk television channels whose owner is a sympathiser of Fethullah Gülen’s movement, the attack on the offices of the well-known newspaper Hürriyet by stone-throwing AKP supporters, or the arrests of foreign journalists covering the conflict with the PKK, raise fears that the Executive has initiated a press-gagging campaign against those opposed to the AKP. Were this the case, it would seriously harm the legitimacy of the upcoming elections.